Through a battery storage system of under to over 2,500 operating hours: When is the jump worth it – and when does it become a cost trap?

Jan 6, 2026

The usage hours determine whether a company is classified as a low user (under 2,500 h/a) or high user (over 2,500 h/a). It sounds like a formality, but it can make a difference of several thousand euros per year because the net fees change depending on the classification.

Under 2,500 h/a, it is typically the case: low performance price, high energy price.

Over 2,500 h/a, it is typically the case: high performance price, low energy price.

This article explains how usage hours are calculated and why there is this "kink".

This post addresses the practical question: Is it better to be under or over 2,500 h/a – and when does it make sense to exceed this threshold with a battery storage?

What are usage hours (short and understandable)?

Usage hours result from annual consumption (kWh) divided by the annual peak power (kW).

Example: With an annual consumption of 1,000,000 kWh and a peak power of 450 kW, there are 1,000,000 / 450 = 2,222 usage hours per year. This is below 2,500 h/a, thus a low user.

The big question: Stay below or go over?

Many think: "Under 2,500 h/a is certainly cheaper." This is not always true. The reason is simple: The electricity costs fundamentally consist of two levers.

Energy price (Euro per kWh): affects every kilowatt-hour in the year

Performance price (Euro per kW and year): affects the peak power

If the energy price in the high user tariff is significantly cheaper, it can offset or even overcompensate for the higher performance price. To quickly get a sense without complicated calculations, a simple traffic light rule is helpful.

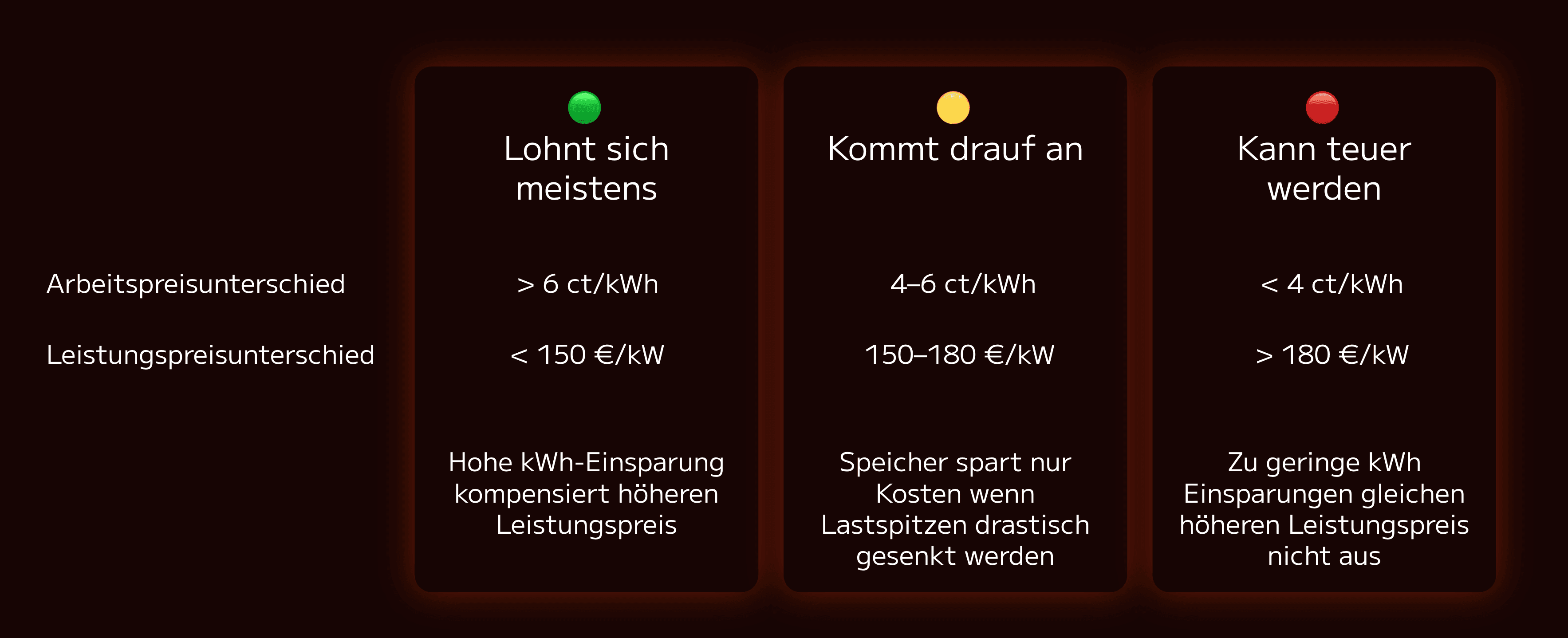

Traffic Light Rule: When is "over" good – and when dangerous?

🟢 Green: Going over is usually worth it

This is often the case when the energy price advantage in the high user tariff is large, for example, at least 6 ct/kWh. Then every kilowatt-hour consumed saves so much that the higher performance price is compensated in many cases.

🟡 Yellow: It depends

This area typically occurs when the energy price advantage is only medium-sized, about 4 to 6 ct/kWh, and the performance price rises significantly at the same time. The economics then strongly depend on how much the storage actually lowers the peak power. In this area, a quick calculation is almost always worthwhile.

🔴 Red: Going over can become a cost trap

This often happens when the energy price advantage is small (under 4 ct/kWh), but the performance price rises sharply. Then you suddenly pay significantly more per kW, but don’t save enough on kWh to compensate.

Before below – with storage above: Calculation example (1,000,000 kWh/year)

To understand when jumping over 2,500 usage hours is worthwhile, a concrete example is helpful. In this case, only the peak power is reduced through peak shaving with battery storage. The annual consumption remains the same.

1) Starting position: Without storage (low user)

Assumptions:

Annual consumption: 1,000,000 kWh

Peak power: 450 kW

Usage hours: 1,000,000 / 450 = 2,222 h/a

Classification: low user (under 2,500 h/a)

Typical tariff logic in this area:

low performance price

high energy price

2) With battery storage: Peak drops significantly (high user)

Now a battery storage is used that reduces the peak power.

New assumptions:

Peak power (with storage): 300 kW

Annual consumption: unchanged 1,000,000 kWh

Usage hours: 1,000,000 / 300 = 3,333 h/a

Classification: high user (over 2,500 h/a)

Typical tariff logic in this area:

low energy price

high performance price

The crucial point is: Whether the switch actually brings advantages depends on how much the energy price falls and how much the performance price increases. That’s exactly why the same storage use can be very sensible depending on the tariff structure – and in other cases can become a cost trap.

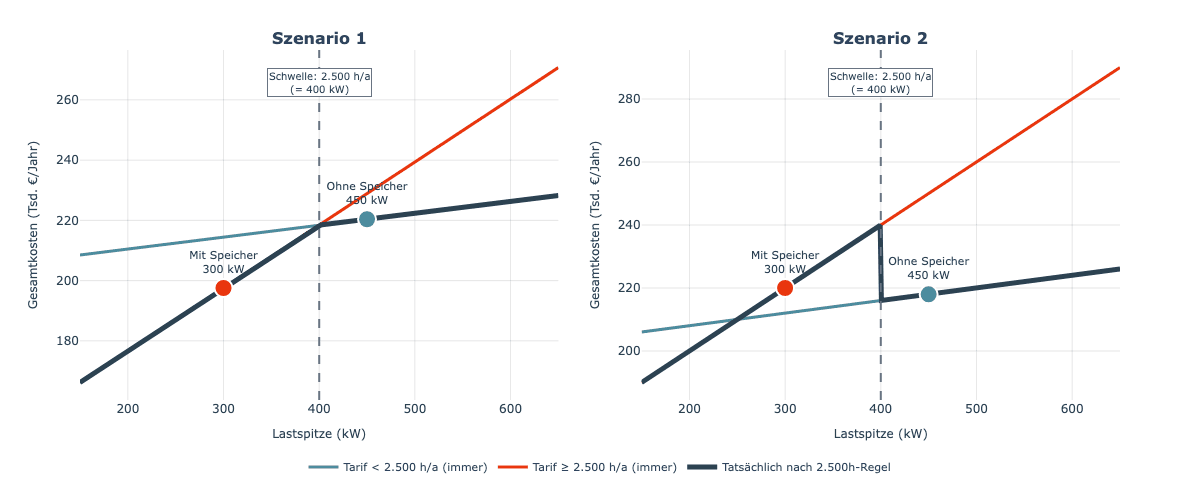

Two typical tariff structures: When is the jump uncritical – and when dangerous?

To clarify why the switch over 2,500 h/a is not automatically "good" or "bad", two scenarios with different prices help.

✅ Scenario 1: "Over" is usually uncritical (large energy price advantage)

In this tariff structure, the energy price in the high user tariff is significantly cheaper. The advantage in kWh is so large that it can frequently compensate for the higher performance price.

Example tariff:

Under 2,500 h/a: Energy price 0.2026 €/kWh, performance price 39.46 €/kW·a

Over 2,500 h/a: Energy price 0.1348 €/kWh, performance price 209.12 €/kW·a

Costs:

Without battery storage:

Energy price: 1,000,000 kWh * 0.2026 €/kWh = 202,600 €

Performance price: 450 kW * 39.46 €/kW·a = 17,757 €

Total: 220,357 €

With battery storage:

Energy price: 1,000,000 kWh * 0.1348 €/kWh = 134,800 €

Performance price: 300 kW * 209.12 €/kW·a = 62,736 €

Total: 197,536 €

➡️ In this example, the total costs decrease from 220,357 € to 197,536 € through the storage. This corresponds to a savings of 22,821 € per year. The reason is the significantly lower energy price in the high user tariff. At the same time, the storage reduces the peak power, so that the high performance price is applied to fewer kW.

❌ Scenario 2: "Over" can become a cost trap (small energy price advantage)

Here, the energy price in the high user tariff only drops slightly, while the performance price rises sharply. Then it may happen that the tariff switch ultimately costs more despite peak shaving, because the performance price overshadows the small kWh advantage.

Example tariff:

Under 2,500 h/a: Energy price 0.20 €/kWh, performance price 40 €/kW·a

Over 2,500 h/a: Energy price 0.16 €/kWh, performance price 200 €/kW·a

Costs:

Without battery storage:

Energy price: 1,000,000 kWh * 0.20 €/kWh = 200,000 €

Performance price: 450 kW * 40 €/kW·a = 18,000 €

Total: 218,000 €

With battery storage:

Energy price: 1,000,000 kWh * 0.16 €/kWh = 160,000 €

Performance price: 300 kW * 200 €/kW·a = 60,000 €

Total: 220,000 €

➡️ Despite peak shaving, the total costs in this example rise from 218,000 € to 220,000 €. That’s an additional cost of 2,000 € per year. While the energy price saves 40,000 €, the performance price simultaneously increases by 42,000 €. The kWh advantage is too small in this scenario to compensate for the kW jump.

Conclusion: It depends on the prices

The same battery storage can either provide significant savings or increase electricity costs for a company slightly below 2,500 h/a. The crucial difference is not the 2,500 hours threshold itself, but the specific tariff structure of energy price and performance price in the respective network area.

It is important to note that even if the jump over 2,500 h/a, as in scenario 2, is isolated to lead to higher costs, a battery storage can still be worthwhile in the overall concept. In practice, the storage is usually not only used for peak shaving but can also unlock additional revenue and savings potentials, for example, through self-consumption optimization, arbitrage in dynamic tariffs, or participation in flexibility and ancillary services markets. Those who include these additional use cases can have a positive outcome overall even with an unfavorable 2,500h tariff switch. More on multi-use here.

In practice, it is therefore always worthwhile to do a quick check: Is the energy price advantage in the high user tariff large enough to compensate for the higher performance price and what additional revenue sources or savings can the storage realistically generate?